How to choose a company you'll thrive at

Picking the next unicorn doesn't help you much if you hate it there

Plenty has been written about how to choose a company to join, especially for startups.

These articles usually focus on factors that predict the startup’s success so you can join a rocket ship 🚀 instead of a Hindenburg 💥.

But those factors don’t determine whether you’ll be happy there. And if you’re not happy, you:

Can’t do your best work, and

Likely won’t stay long enough to vest all of your equity.

So even if you’re purely optimizing for financial outcomes, you need to look beyond just the (probability of) success of the company you’re choosing. Picking a high-caliber company is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition.

The focus of this post is to plug that gap and cover the other factors that matter in choosing a company to join. In addition, I’ll also touch on how to actually get that information.

Let’s dive in.

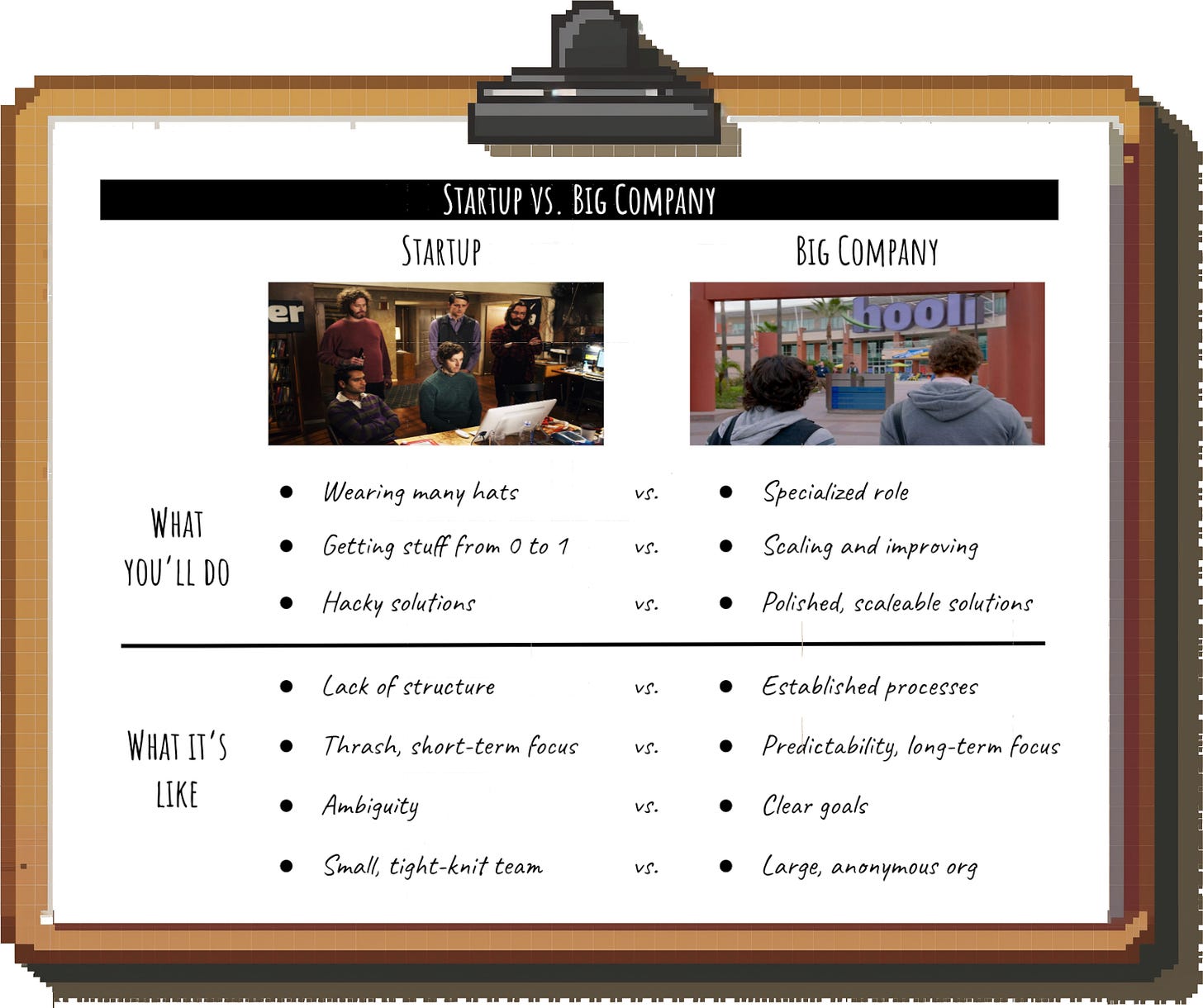

Company stage

The company stage is the aspect that will affect your experience the most.

At every job I took I tried out a different company stage, going from a 10-person startup to pre-IPO scale-ups and big tech companies. The experience was drastically different although most of the time I was in the same type of role (Strategy & Analytics).

The company stage affects both what you do, and what the environment is like:

The only way to figure out what environment you thrive in is to try it out. Pick your first company, and then go bigger or smaller next time based on that experience.

One underrated option is to go for a middle ground: a new venture within a larger company. For example, I joined UberEats when it was a fast-growing “startup” within Uber.

This can give you a unique hybrid environment; for example, most of the work at UberEats at the time was 0 → 1 (launching new markets and delivery offerings), but we were building on top of the existing Uber platform and had the resources of a big corporation.

Organizational structure

Which function calls the shots?

It’s more fun working at a company where your function has a seat at the table.

Engineering has an outsized influence at basically every tech company, but there are pretty big differences in how powerful other functions are. Power dynamics also shift over time.

Here is an example from my experience at Uber:

In the early days, General Managers (responsible for a given market) and their Operations teams basically ran the show. A big reason for this was that many key activities like setting pricing, incentives and dispatch configurations were handled manually by Ops teams. Over time, though, more and more of those processes could be automated.

With increased automation, the Product org became more and more influential. By the time I left, it felt like the power dynamic had shifted in Product’s favor. Where before Product had to pitch Ops teams on their solutions, Ops now had to justify any instance where a productized automation was overridden.

Where to get this information: You’ll get the most honest take from people who recently left. You can find these folks on LinkedIn by either searching for people who used to work at your target company or looking for their job-switch announcement posts.

Are teams like Data Science and Strategy / Ops centralized or embedded?

If you’re in DS or BizOps, you need to understand where these functions sit in your target company.

Being part of a centralized function means you’ll have more opportunities for getting mentorship, learning best practices etc.. On the flip side, it will be harder to develop deep expertise in the business areas you’re supporting and you’ll often feel like an outsider rather than part of the team.

Where to get this information: Just ask for an overview of the org structure during the interview process. Some follow-up questions to consider:

If the function is centralized:

How do you get close to the work of the teams you partner with? Without detailed business context, you cannot add value

How does planning work? Are individuals dedicated to a specific team they support, or are resources allocated flexibly across all requests?

If the function is embedded:

How does career development work? Is it possible to move between teams (e.g. from Marketing DS to Product Analytics)? How do you develop your core skill-set if you are the only DS or BizOps person on the team?

How does the company avoid duplicative work and ensure best practices are being followed?"

Who are you calibrated with during performance cycles? The team you’re embedded in or all other DS / BizOps folks across the company?

Management & career growth

Are managers in the operational weeds or just people managers?

It feels very different to work at a company where managers just focus on planning, allocating work, developing people etc. vs. a company where managers are deep in the weeds and get involved in day-to-day decision-making and execution.

For example, many General Managers or Directors at Uber were hands-on; they would run SQL queries to get the data they need and debate the pros and cons of tactical decisions like city-specific dispatch settings with their teams. The same was true at Rippling. In contrast, at Facebook I found that many managers were focused on the bigger picture and left the tactical details to their team.

There are pros and cons to either version, you just have to decide which one is a better fit for you:

Does the company have a track record of promoting from within?

Most companies claim that they have great growth opportunities, but in reality, they tend to hire external candidates for key positions rather than promoting from within.

Where to get this information:

You can easily do some checks yourself.

Look up the LinkedIn profiles of all the managers on your interview circuit; how many of them got promoted from IC roles into their position vs. hired?

Look up the executives of the company; how many have worked their way up vs. were recruited?

Is management a requirement to get ahead?

Not everyone wants to be a manager, but not every company gives you a choice.

In my last company, there were Individual Contributors (ICs) up to Senior Director level even outside of Engineering in functions like BizOps. Unfortunately, this is the exception rather than the rule. Many companies offer parallel tracks for senior ICs and managers only for Engineers, if at all.

Before you join, make sure your desired career path is even possible.

Where to get this information:

Ask the hiring manager for a walk-through of the leveling system and career paths. Ideally they can point you to senior ICs in your function that show that this is actually an option in practice

Is there internal mobility between teams?

Some companies encourage internal mobility, some restrict it.

In my experience, it’s a clear positive if a company is supportive of internal moves. If you are a manager, you might “lose” a few folks to other teams over time, but it creates an incentive to run a team with an exciting mandate and a strong culture.

And it creates great opportunities for individuals; my promotion to Director came as part of an internal transfer from BizOps to Marketing.

Questions to ask:

Official policies are less helpful here. Ask for specific examples of people who moved between teams or functions; if it’s something that’s encouraged, people will have an easy time answering this

Culture

Everyone agrees “culture” is important, but it’s this vague term that’s hard to make sense of. Below are some of the key dimensions that define what culture feels like day-to-day.

Where does urgency come from?

Every job worth doing has intense periods and urgent requests from time to time. But not all emergencies are created equal.

For example, when I worked at Rippling, there was an almost company-wide fire drill due to the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank; funds that were supposed to be paid out to the employees of companies using Rippling’s payroll product were being frozen instead. Over the weekend, Rippling raised additional funds from investors and switched from Silicon Valley Bank to JP Morgan to make sure customer employees get paid.

That’s actually urgent and a reason to work over the weekend.

An ask from a stakeholder at 5PM on Friday to pull some numbers for a deck (because they forgot to ask earlier) is not actually an emergency.

Try to find a company that has a reasonably high bar for “urgent”.

Questions to ask:

“When was the last fire drill you were involved in? What was it about?”

How are decisions made?

In my experience, a lot of frustrations at work come from how companies make decisions.

The fewer decisions you are empowered to make yourself, and the more hoops you have to jump through to get bigger decisions made, the less stuff you’ll get done.

Couple this with unclear processes and responsibilities (e.g. how do you proceed if two teams disagree) and you have the perfect recipe for frustration.

Questions to ask:

Autonomy: Ask people you interview with about the biggest decision they made completely by themselves (without buy-in or approval from anyone)

Disagreement between teams: Ask about the last time two teams disagreed. How was this resolved? Do they use a framework like RAPID or RACI to clarify roles?

Does the best idea win? Ask the more junior folks you’re talking to about the last time they convinced somebody substantially more senior (Director+)

Reversed decisions: Ask about the last time a decision was reversed. What led to this?

What is the data culture like?

If you are in an analytical role, understanding the data culture of the company you’re considering joining is crucial.

Here are the key factors to consider:

1. How is data used in decision-making?

The ideal environment, in my experience, is one where rigorous, large-scale data analysis is combined with “going and seeing” (talking to customers, looking at support tickets, reading deal notes etc.).

Each by itself can quickly lead to problems.

Data analytics has limitations, and companies that don’t acknowledge this are prone to making poor decisions. In addition, you will spend a lot of time mining the available data for something useful instead of learning to think from first principles and use judgment.

A company that doesn’t use data in decision-making isn’t a great place for an analyst or data scientist, either. In the worst case, you’ll find yourself unable to influence decisions at all. Best case, you’ll be asked to tweak the data to support an already developed narrative.

Questions to ask:

“When was the last time you found an unintuitive trend in the data? What did you do about it?”

“Can you give me an example of a piece of data that changed your mind recently?”

Ask questions specific to your domain; e.g. if you’re in Marketing, ask “How do you decide how to allocate your Marketing budget?”

2. Is there any self-serve data access, or does everything go through the data team?

At Uber, almost everyone wrote SQL and would pull their own data. At other companies I worked for, things were much more centralized.

This affects you whether you are on the data team or not. If you’re on the data team and there is no democratized data access, you’ll inevitably spend a lot of time doing ad-hoc data pulls and building an endless number of dashboards for stakeholders.

If you’re on a business or product team, the data team will become a bottle neck, making it difficult for you to get the insights you need.

Questions to ask:

What BI tools does the company use? Tools like Omni, Sigma and Mode suggest more self-serve access, while Tableau and Looker are a sign of heavy reliance on the data team

What access will you get? If you get access to all relevant tables in the data warehouse, the main blocker to you getting the data you want (regardless of the BI tool the company uses) will be your SQL skill level

Meeting culture

The daily routine a lot of us go through:

You’re stuck in meetings all day, and the actual work only happens after dinner. And to make things worse, it feels like many of the meetings weren’t even productive.

Luckily, it’s not like that everywhere.

Questions to ask:

“When was the last meeting you thought was unproductive? What was the problem?” Bad meetings are an unavoidable part of work; if people reflect on the issues and try to improve, though, at least you’ll have some allies in trying to fight this problem

Ask your interviewer how much time they spent in meetings this week. If they don’t know, ask them if they’re comfortable pulling up their Google Calendar Time Insights:

How transparent is the company?

Joining Uber was an eye-opening experience for me. I first joined as an intern, and even though I was a nobody with a three-month contract, I was allowed to go anywhere, attend all-hands meetings (including the juicy ones while the board was battling Travis Kalanick), was on the email list for all important company-wide announcements etc.

In addition, employees could ask any questions they wanted during weekly live Q&As.

I was not used to this; in Germany, where I had started my career, information is often shared on a “need-to-know” basis. But once I had seen how transparent companies can be, I can’t imagine going back.

A few benefits of a transparent company culture:

It creates a much stronger sense of connection; if you know what’s going on, it feels like “your” company

If you always know what leadership’s priorities are, you can make sure your own work ladders up to them

If you know how the company is doing financially, it helps with your work (e.g. you can better judge the success of headcount or budget asks) and you can gauge how your equity and job security are evolving over time

What to ask (for) during the interview process:

Metrics: Ask for metrics before you accept an offer. The company should be willing to share key figures like revenue, growth rates, funds raised and runway etc.. Also: Does leadership regularly share financial updates with the company?

Access: Are any parts of the campus off-limits?

All-hands and Q&A: Who can attend all-hands meetings? Is there a Q&A to ask (uncomfortable) questions to executives directly?

Memo / slides culture

Much has been written in recent years about how memos are (supposedly) superior to slides. You can check out Jeff Bezos’ take and his explanation of Amazon’s 6-page memos here:

The organizational benefits are beyond the scope of this post, but in my experience there are two key advantages for individuals in memo-heavy cultures:

It’s much easier to learn. If you come a cross a random deck (e.g. on a planned product launch), it’s often hard to really understand things without anyone presenting the slides. A crisp memo that lays out the thinking in narrative form, on the other hand, can be a great substitute for an in-person conversation.

Less time tweaking slides. If slides are heavily used, there’s a big risk that you’ll spend a lot of time tweaking the formatting, trying to squeeze in all relevant information etc. rather than doing actual work. With memos, which are mostly text with a few charts here and there, that is much less of an issue.

One thing to keep in mind: While the discussion is often framed as “memos vs. slides”, very few companies are so extreme in practice that they ban slides completely or don’t write any narrative documents at all.

What matters is that memos are the preferred medium for your day-to-day deliverables; e.g. if you’re a PM, it matters more whether product strategy is written in memo form than whether the Board of Directors gets a slide deck from Finance once a quarter.

In-office vs. remote culture

There are a few considerations here:

What’s the official in-office requirement?

This is not just the number of days, but also whether specific days are required. I also recommend checking whether the policy has changed in the past, esp. if you’re counting on being remote on certain days (e.g. for child care).

How strictly is this being enforced?

There’s a difference between an expectation that you’re on average in the office a certain number of days and the company tracking your badge data and emailing your manager if you miss a day.

It’s nice to be able to work remotely for a week every now and then (e.g. over Christmas) without immediately getting into it with HR.

Are there any exceptions?

Some companies allow fully remote employees in addition to in-office or hybrid models. However, you need to understand if this affects your options for career advancement. For example, Dell decided that remote employees are ineligible for promotion.

Compensation terms

Even if the compensation for your role looks good on paper, you might be in for some unhappy surprises based on company policies.

Here are some factors to look out for:

RSU vesting cliff: If you are getting Restricted Stock Units (RSUs) as part of your compensation package, they will vest over time. However, as a new joiner, there will typically be a so-called “cliff”; until you hit that point in time, you don’t vest any RSUs. The longer the cliff, the higher the risk you’ll be left with nothing if you leave early.

Post-termination option exercise window: If you are getting options and leave the company, you have a limited time window to exercise them. If you don’t, you’ll lose them. Exercising options will cost you (potentially a lot) of money in taxes, so make sure you 1) pick a company with a generous policy, 2) negotiate a longer exercise window or 3) save up for this scenario.

Here’s a real-life example of someone who had to shell out $300k to keep his options when he left a high-growth company pre-IPO.

Closing thoughts

Picking a winning company is not the only thing that matters; if you want to avoid burnout and stay long enough to vest your stock, you need to pick a company that you’ll actually enjoy working at.

Hopefully the considerations above help you in finding a place where you’ll make bank and thrive.

Like the actionability from this article Torsten!

The questions to ask and figures made this article very effective.

I also found that asking a prospective manager about the worst blunder they had to deal with and how they handled it gives good insight into how mistakes are handled in the team's culture. I personally like being part of environments where mistakes are treated as opportunities to learn and improve the process rather than an opportunity to play the "blame game".

I also would add asking about how kudos/adhoc recognition are communicated too. It's good to be part of a place where you feel appreciated